Remembering Three Towering African Musicians

Curators reflect on the lives of Aurlus Mabele, Manu Dibango, and Tony Allen with playlists of their music and the songs they inspired.

Ugochukwu-Smooth C. Nzewi, Josh Siegel

May 28, 2020

Curator Ralph Rugoff titled the theme of his 2019 Venice Biennale “May You Live in Interesting Times.” The title, an old English phrase that had long been misattributed as an ancient Chinese curse, is apropos for our current uncertain, tumultuous situation. COVID-19’s harmful footprint has spared no corner of the world, leaving it forever changed. According to artist Olu Oguibe, “In times of sadness, grief, or great trauma, it’s to beauty that we turn. We send flowers. We leave flowers. We share stories. In times of plenty as well as want, we sing and we make marks. When we’re quarantined and there’s nowhere to go, nature leaves us the escape hatch of imagination. That’s why art is essential, and not a privilege. That’s why art endures.” Here, we reflect on the legacy and music of three influential African musicians, Aurlus Mabele, Manu Dibango, and Tony Allen, who died recently, two of the coronavirus, but whose innovative musical impact will be felt around the world forever. We celebrate their lives through playlists that spotlight their songs and the global musicians they collaborated with and inspired.

Aurlus Mabele

AURLUS MABELE (October 26, 1953–March 19, 2020)

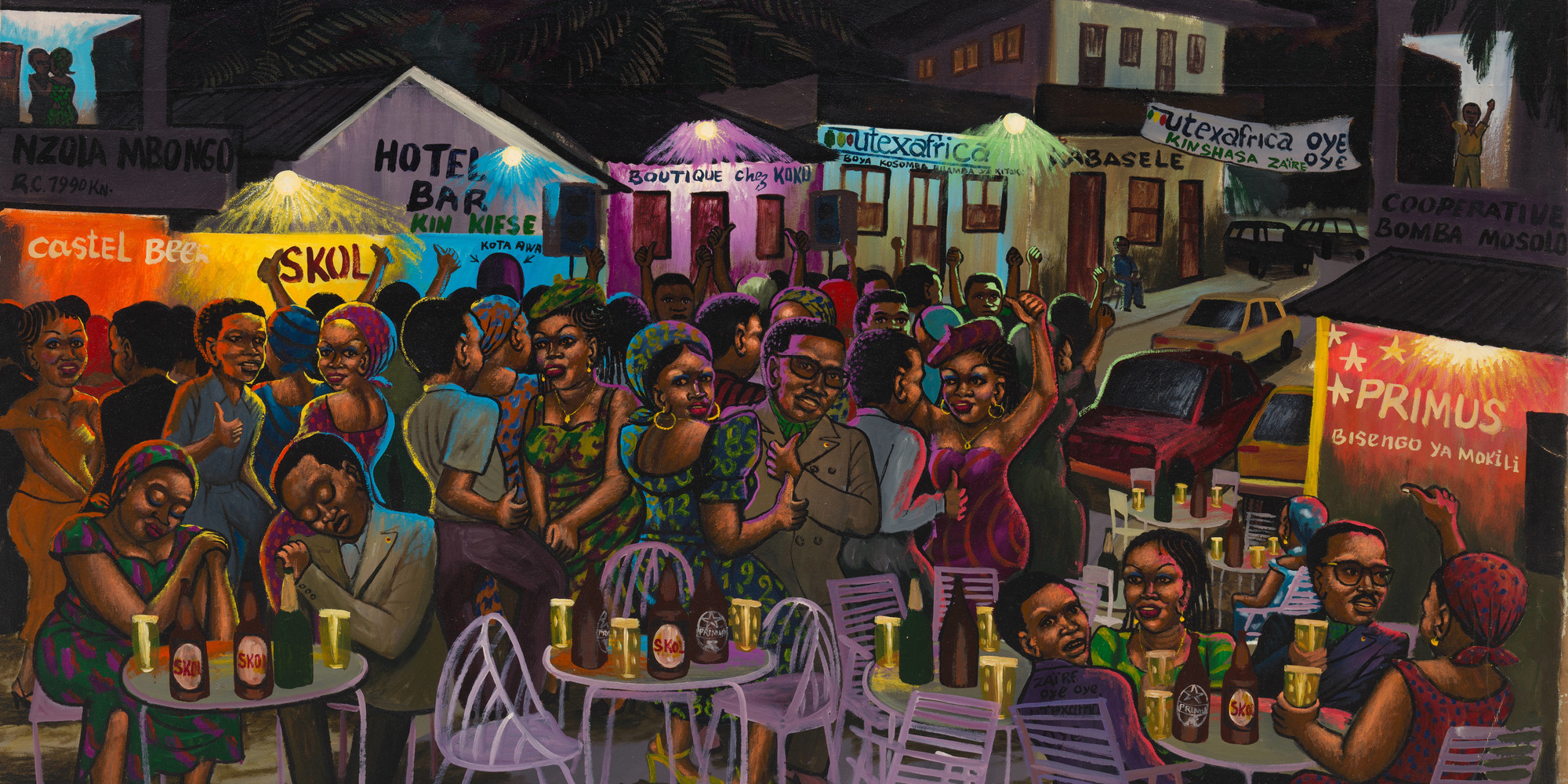

Known far beyond his native Congo-Brazzaville as the King of Soukous, Aurlus Mabele was as flamboyant a dancer as he was a singer, composer, and bandleader. Dressed in natty, loose-fitting clothes of his own design, Mabele stood out among the Kinshasa-bred sapeurs, Congolese dandies obsessed with fine garments, who took Paris by storm in the 1980s.

The uniquely Congolo-Zairean soukous was born on the banks of the Congo River in the twin capitals of Brazzaville (the Republic of the Congo) and Kinshasha (the Democratic Republic of the Congo). An up-tempo dance music syncretized from American R&B and funk, numerous Caribbean genres (bélé, mérengue, soca, beguine, modern chouval bwa, and cadence-lypso), and West African influences including the Baluba folkloric music of Mabele’s own people, its name, appropriately enough, comes from the French word secouer, meaning “to shake.”

Mabele was born Aurélien Miatsonama into a family of musicians and artists in Congo-Brazzaville on October 24, 1953. In 1974 at the age of 21, he founded the popular Brazzaville band Les Ndimbola Lokole alongside Mav Cacharel, Jean Baron, and Pedro Wapechkado. (Our Spotify playlist includes their most celebrated songs, “Embargo,” “Waka Waka,” and “Zebola,” which are sure to get you on your feet.) After settling in Paris in 1980, Mabele became a top session player for Kanda Bongo Man and other African diaspora musicians who were experimenting and recording at the legendary Studio Caroline. In 1986, he formed the supergroup Loketo—meaning “hips” in his native Lingala—together with the powerhouse electric guitarist Diblo Dibala, the singers Jean Baron and Mav Cacharel, and Mack Macaire on drums (various others, including Komba Bellow, Ronald Rubinel, and Freddy De Majunga, drifted in and out of the group before it disbanded in 1990). Loketo sold some 10 million albums and toured the world. They became a fixture of dance clubs in Europe and the Americas during the 1980s: at New Morning in Paris and SOBs in New York City, at the Maroni Palace in the French Guianese capital of Saint-Laurent (where Mabele’s band inspired the development of loketo, a catchy fusion of soukous and local kaseko), and in Martinique and Guadeloupe (where the band Kassav’ was busy making zouk a wildly popular French Antillean variant of soukous).

Mabele’s great contribution to soukous was to dispense with the music’s slow introduction and launch right into the kinetic instrumental dance groove, led by guitar and drums (known as the sebene). Against a thrumming beat and Diblo Dibala’s propulsive arpeggio guitar licks, Mabele would let loose, putting his own spectacular stamp on dances like kwassa kwassa, madiaba, and soundama, and singing effortlessly among the languages of the Central African Republic, English, French, and Creole, depending on his audience.

Mabele’s health had been failing for several years before he succumbed to the coronavirus in Paris on March 19, 2020. He was 66.

Manu Dibango

MANU DIBANGO (December 12, 1933–March 24, 2020)

In 1972, the year that Cameroon became a unitary republic, Manu Dibango released “Soul Makossa.” Intended merely as the B-side of an anthem for the Cameroonian football team at the Tropics Cup, it became the first African pop song to hit the Western Top 40 charts. (It would be the last for many years to come.) You probably know its infectiously danceable Douala chant “ma ma ko, ma ma sa, ma ko ma ko sa”—one of the most recognizable hooks in music history—from Michael Jackson’s “Wanna Be Startin’ Somethin’,” Rhianna’s “Don’t Stop the Music,” and countless other songs that have sampled it. (This diagram maps out the extraordinary lineage.) Only after a threatened lawsuit did Jackson acknowledge—and pay—Dibango for the inspiration, an all-too-familiar refrain for so many African musicians.

While lesser Western songwriters treated African pop music as a form of cultural tourism, seeking an authentic “African sound,” Dibango was a restless experimenter who moved nimbly among various genres.

Far from a one-hit wonder, though, the Cameroonian saxophonist, vibraphonist, pianist, and songwriter produced more than 60 albums between 1968 and 2013, successfully integrating African popular music in its many varied forms, absorbing and imbricating the complexities of American jazz, funk, R&B, and soul; Cuban salsa and highlife from Nigeria and Ghana, Congolese soukous and Cameroonian makossa (the music of dance clubs and grilled fish houses), Jamaican reggae and Brazilian bossa nova, French chansons, French-Caribbean zouk, Algerian raï, and Indian raga with jazz and other Western musical idioms. These hybrids and crossovers became a global phenomenon as diverse international artists, looking to expand their musical horizons, sought Dibango’s collaboration: the jazz legends Art Blakey and Don Cherry; Harry Belafonte, Miriam Makeba, Ladysmith Black Mambazo, and other pop singer-songwriters like Paul Simon, Stevie Wonder, Serge Gainsbourg, Peter Gabriel, and Johnny Clegg; the seminal Congolese rumba group Africa Jazz, led by Joseph Kabasele; the Nigerians Fela Kuti, Tony Allen, and King Sunny Adé; the Jamaican reggae producers Sly Dunbar and Robbie Shakespeare; and the Cuban guitarist Eliades Ochoa, as well as Ousmane Sembène, Flora Gomes, and Ossie Davis, for whom he composed film scores. Our Spotify sampler features some of the best of these.

While lesser Western songwriters treated African pop music as a form of cultural tourism, seeking an authentic “African sound,” whatever that is—“Being an African musician means you play tam-tams; beyond that, no admittance,” Dibango observed ruefully—Dibango was a restless experimenter who moved nimbly among various genres and became an accidental ethnomusicologist to a great many talented artists.

Born Emmanuel “Manu” N’Djoké Dibango on December 12, 1933, in the Cameroonian port city of Douala, Dibango was of mixed ancestry: a Protestant in a largely Catholic country, his father from a farming family in the Yabassi tribe and his mother an urbane fashion designer of Douala descent. Working his way to international fame from jazz and dance clubs in Douala, Léopoldville (Kinshasha), Brussels, and Paris, and at various times calling cities throughout Europe and Africa his home, Dibango never lost his sense of being a stranger in a strange land: “A black American in France, an African in the United States, a European in Africa—it’s the labeling dance,” he would often tell interviewers. But rather than smoothing out the tensions within his own biography and among the diverse cultures of Africa and the West, Dibango found a way to throw the contradictory aspects of his identity into higher relief through music. Dibango saw himself as a “Négropolitain,” writing in his excellent 1989 memoir Three Kilos of Coffee that “when West Africa talks of ethics, it advocates a return to roots. This is a facile solution which goes nowhere. I would accept it if it opened up a new path. We have never left our roots. Like all continents, Africa has its past; like others, it has been colonized. That time is over. Creativity is our only path to health—making way for the imagination.”

Manu Dibango died of the COVID-19 virus in France on March 24, 2020. He was 86.

Tony Allen

TONY ALLEN (August 12, 1940–April 30, 2020)

Bass, snares, dub-inflected electronics, effusive funk, and syncopated drumming: Tony Allen’s rhythmical complexity and hypnotic flare need little introduction for devotees of Afrobeat, which is arguably the most popular music genre to come out of Lagos, Nigeria, in the mid-20th century.

Early 1960s Lagos was a live wire of culture fueled by Nigeria’s attainment of political independence. As the capital of the new postcolonial nation, Lagos was a crucible of several new and modern music genres, of which highlife—a syncretic music form that drew from swing, regimental band music, Christian hymns, Caribbean calypso, Afro-Cuban percussion, bebop, modern jazz, and wide-ranging West African music traditions—was the most notable. Allen was part of this emergent, lively cultural scene. Although he played on the Lagos club circuit, he got his professional break with the Cool Cats Band (subsequently known as the All-Star Band) of the late highlife maestro Victor Olaiya (who died in February 2020). The venerable Olaiya was one of the most influential musicians in that period, mentoring a slew of highlife crooners who would go on to achieve immense success. It was during this time that Allen met the multi-instrumentalist and human rights activist Fela Ransome Kuti (later Anikulapo Kuti), the creator of the Afrobeat genre, who was under the tutelage of Olaiya. Allen joined Kuti’s highlife band Koola Lobitos in 1964. The band later evolved into the groundbreaking Afrika 70, which would be identified by its unmistakable new sound, called “Afrobeat.” Afrobeat grew out of Kuti’s earlier highlife experiments and his exposure to the rhetoric of the Black Power movement during a 10-month sojourn in Los Angeles during 1969. The mélange sounds of Afrobeat comprise jazz, salsa, West African highlife, and Yoruba high-tension drumming conventions; and are defined by Allen’s incomparable polyrhythmic funk drumming—especially in the 1970s, the most critical decade in the genre’s development.

Allen departed Afrika 70 to form his own band in 1980, heralding his post-Fela era with No Discrimination, featuring a laid-back, propulsive sound that retains the call and response format of his previous work. However, its socially conscious message, sung in the genre’s signature pidgin English, lacks the directness and fervent punch of Fela Kuti’s diatribes against social injustice, political oppression, and neocolonialism. Allen migrated to Europe, and over the next 30 years would come into his own as a bona fide international star and leader of the genre, constantly evolving its form and expanding its reach through collaborations with musicians of other genres such as pop, electronica, rock, jazz, and rap.

Allen’s numerous collaborations made him a preeminent crossover specialist and brought him massive mainstream attention. Our playlist features a selection of Allen’s solo recordings, collaborations, and associated acts, including fellow African stars such as Fela Anikulapo Kuti, Manu Dibango, King Sunny Adé, Hugh Masekela, Ebo Taylor, Ray Lema, and Oumou Sanagare; and non-African collaborators including Moritz von Oswald Trio, Jeff Mills, Jimi Tenor, Ernest Ranglin, Damon Albarn, Flea of the Red Hot Chili Peppers, Paul Simon, Simon Tong, Gorillaz, and Skepta.

Born into a middle-class Lagos family on August 12, 1940, Tony Oladipo Allen was largely self-taught and developed his signature style by listening to jazz greats of the bebop era such as Art Blakey and Max Roach, as well as the ace Ghanaian drummer Guy Warren. The legendary drummer died on April 30, 2020, in the Parisian suburb of Courbevoie, where he had lived since 1985. He was 79 years old.