“I felt the great scream in nature.”

Edvard Munch

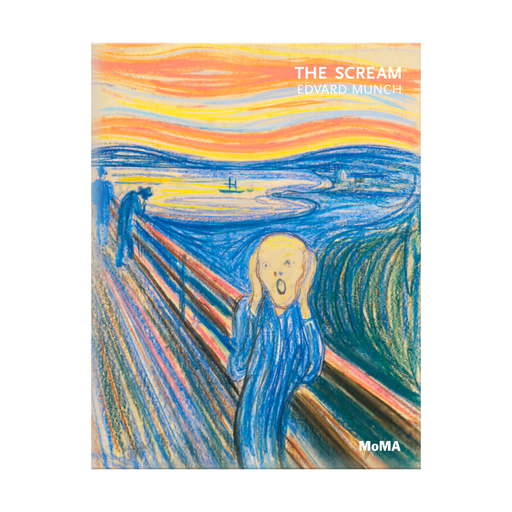

For Edvard Munch, 1893 was a year of screams. In the fall, the Norwegian artist produced two versions of The Scream, his now iconic image of personal and universal anguish. “You know my picture, The Scream?” he later wrote. “I was being stretched to the limit—nature was screaming in my blood—I was at a breaking point.” The same year, Munch painted The Storm. Set in a coastal village south of Kristiania (now Oslo), where the artist spent many of his summers, the canvas depicts a windswept landscape in which several women stand with their hands pressed against their faces in the same manner as the tormented figure in The Scream. Common to both compositions is a keen interest in the relationship between inward and outward realities. In The Scream, the figure’s silent shriek seems to reverberate through the undulating streaks of brilliant pigment that define the surrounding hills, bay, and sky. Likewise, the gusts of air that sweep across the shoreline in The Storm appear to be at once physical and metaphysical, atmospheric and psychic. In each case, Munch poses a question that he would pursue until his death in 1944: To what extent can artists convey their innermost thoughts and feelings using lines, forms, and colors?

By 1893, Munch had contemplated this question for over a decade. Following a difficult childhood in which his mother and sister died of tuberculosis and he himself was often ill, the teenage Munch studied to become an engineer at his father’s urging. Despite excelling in mathematics, physics, and chemistry, it was technical drawing that thrilled him. Eventually, he left the professional school where he had been enrolled, writing in his diary in 1880, “I have decided to become an artist.” Then living in Kristiania, Munch enrolled at the Royal School of Art and Design and soon began to show his paintings alongside the city’s small but dynamic avant-garde. Travels outside of Norway followed, allowing Munch to participate in international exhibitions from Belgium to France to Germany while immersing himself in the art of his predecessors and contemporaries at museums, galleries, studios, and academies throughout Europe. “Here I am in Paris,” the artist wrote to his aunt during one such trip. “I think I’ll go to the Louvre and the Salon today,” he added, referring to the French national art museum and annual art exhibition, respectively. While in Paris, Munch relished his encounters with the works of Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, Paul Gaugin, Vincent van Gogh, Georges Seurat, and others.

It was in France in late 1889 and early 1890 that Munch, grieving his father’s death in Norway, outlined his artistic convictions in a passionate manifesto. Art, he declared, should strive to portray subjective experiences—experiences of the most profound joy and pain, the most intense pleasure and sorrow. “Interiors should no longer be painted, no people reading and women knitting,” he wrote, dismissing the late-19th-century taste for neat, tidy pictures of neat, tidy sitting rooms. “They should be living people who breathe and feel, suffer and love.” The representation of “living people,” Munch believed, would resonate with viewers who felt alienated by modern, urban life. “People would understand the holy, the powerful in this and they would take off their hat as if in a church,” he predicted. “I want to depict a series of such pictures.” The artist embarked on this series right away, producing a web of interrelated works that he eventually would refer to as “The Frieze of Life.” Returning continuously to select subjects—embracing couples, alluring women, despondent men—Munch sought to delineate the course of romantic love as he saw it, from desire to despair.

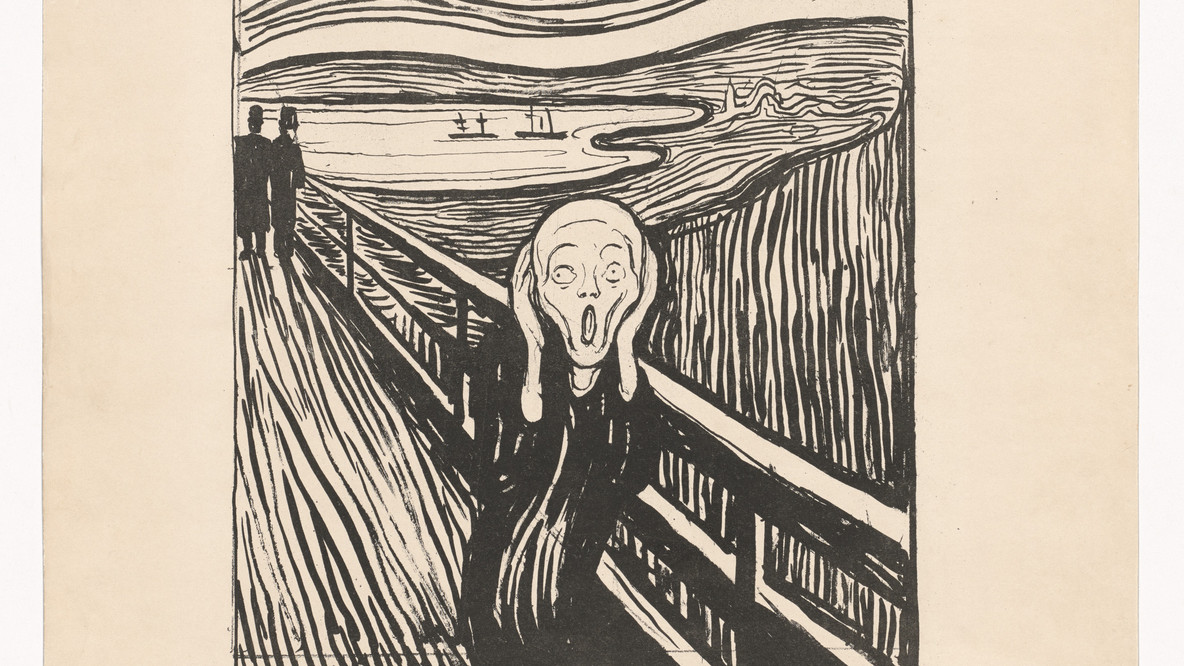

Printmaking was vital to Munch’s Frieze of Life, and to his artistic practice more broadly. He produced his first print, Puberty (The Young Model), in 1894, as artists around the world were developing new printmaking techniques and revisiting existing ones. Munch would do both during his career, ultimately creating over 750 distinct graphic compositions through an array of processes. Like his peers, Munch was attracted to the possibility of generating multiple printed impressions from a single matrix: a physical surface, such as a metal plate, a wooden block, or a lithographic stone, that transfers ink to paper. The Frieze of Life, he realized, could reach a wider audience through prints than through paintings. Moreover, moving between mediums and materials allowed Munch to continually repeat, revise, and reimagine his favorite subjects, articulating the ever-shifting emotions that he considered central to art and life. In a lithographic rendition of The Scream from 1895, for instance, Munch abandoned the screeching hues of his other versions in pastel, oil, tempera, and crayon in favor of simple black stripes. Somber and stark, these marks accentuate the visual meld between the figure and the barren landscape beyond, a quality underscored by the handwritten caption below the image: “I felt the great scream in nature.” For Munch, this was the premise of all great art—“I felt.”

Annemarie Iker, independent scholar, 2020